Rockefeller Center, originally known as Radio City is a complex of buildings developed in the midst of the Great Depression. Initially the complex consisted of 14 buildings, the 70 story RCA building being the tallest.

Metropolitan Opera

The area where the Rockefeller Center is located was originally planned as the new location for the Metropolitan Opera. At the time the area, situated between 48th and 51st streets and Fifth and Sixth avenues was a red-light district owned by Columbia University.

John D. Rockefeller Jr. leased the area on behalf of the Metropolitan Opera, also referred to as 'the Met'.

The design of the complex was created by the American architect Benjamin Wistar Morris. His plan, influenced by the Grand Central Terminal Complex included a landscaped garden and a monumental Opera House as well as tall office towers, shops and terraces. The buildings would be connected by an series of bridges and walkways.

However, the stock market crash of 1929 caused the Met to abandone the ambitious project. Rockefeller then launched a plan for a corporate complex to house the new radio and television corporations. Radio City was born.

Radio City

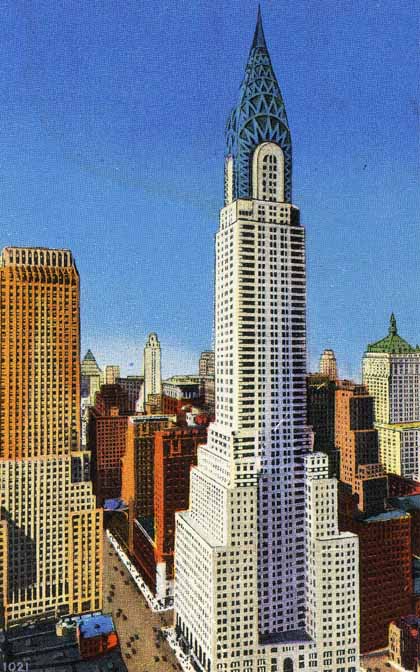

One of the first buildings completed was the RCA building, which served as the headquarters of the Radio Corporation of America. The tower, clad in Indiana limestone, is at 70 stories and 256 meter / 850 ft the tallest of the complex. Its design by Raymond Hood - also known from

the American Radiator Building in New York, the former McGraw-Hill building in New York and the Tribune Tower in Chicago - was the basis for all future buildings at the Rockefeller.

To lure tenants during the Depression, all efforts were made to ensure efficient use of the available floor space. Thanks to the setbacks each office was assured of natural light. Other assets were fast elevators, air-conditioning and excellent underground connections to the subway.

The RCA building is now also known as 30 Rockefeller Plaza or GE Building.

Top of the Rock - the Observation Deck

The Rockefeller Center features an observation deck atop the GE Building with panoramic views of Central Park and the Empire State Building.

When the former RCA building opened in 1933 it featured a roof terrace designed as the deck of an ocean liner. Ventilation pipes were shaped as a ship's chimneys and visitors could relax in deck chairs. The observation deck remained open until 1986. By then the number of visitors had dropped while costs increased. At the same time the expansion of the popular Rainbow Room restaurant on the 65th floor cut off the elevator access to the roof, leading to the deck's closure.

Fortunately the observation deck reopened again in November 2005, finally giving the nearby Empire State Building's observatory some competition. After a renovation of some 75 million dollars, the art-deco style observation deck, promoted as the 'Top of the Rock' can be visited once again; only the deck chairs have disappeared.

A separate entrance at West 50th Street leads to the elevators. In the elevator, important historic events since 1933 are projected on the elevator's transparent roof.

There are in total three levels open to the public, including the roof terrace. The first is on the 67th floor and is completely covered.

The observation deck on the 69th floor has glass windshields while the 70th floor is completely open to the elements, offering visitors a fabulous 360 degree view.

Lower Plaza

By 1940 Radio City, which became known as Rockefeller Center consisted of 14 buildings, located arounda central sunken plaza, the Lower Plaza. From the plaza you have a nice view of the sculpture of Prometheus and the GE building.

Ever since 1933, the famous annual Christmas tree lighting ceremony, which marks the unofficial start of New York's holiday season, has taken place here. The enormous tree, decorated with thousands of lights is installed in the area behind the Prometheus Statue. Around the same time, the sunken plaza is converted into a popular outdoor ice skating rink.

The plaza is connected to Fifth Avenue via a pedestrian street decorated with statues and flowers. This street is known as the Channel Gardens. The Channel Gardens are flanked by two six-story buildings with landscaped rooftops, the British Empire Building and La Maison Française. Another important building in the Rockefeller Center is the Radio City Music Hall. When built, it was the largest indoor theater in the world

with a seating capacity of around 6000. Guided tours give you the opportunity to catch a glimpse of the spectacular Art Deco interior.

A City in the City

Rockefeller Center - known as a 'city in the city' - is an exceptional example of civic planning. All buildings share a common design style, Art Deco, and are connected to each other via an underground concourse, the Catacombs. The complex is nevertheless well integrated in the city of New York, especially along Fifth Avenue. In 1959 and the early seventies, Rockefeller Center was extended with 5 additional buildings along sixth Avenue.